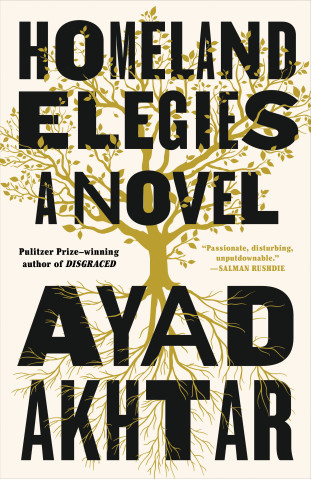

A Review of Homeland Elegies by Ayad Akhtar. Little, Brown and Company, 2020.

Regardless of where we think we fall on the continuum of civility, one thing is certain, we can’t assume that we understand others automatically or that they understand us. In the places where we cross paths with strangers, faulty perceptions and skewed conclusions are ever-present. Ayad Akhtar’s Homeland Elegies does a brilliant job of playing out this conundrum in the experience of immigration.

The author considers himself authentically American, a child born in the United States and a man shaped in its culture. But he is also an immigrant son, and that allows him to see a complication in American identity. In the words of one of his characters Akhtar says, “The thing I never got used to here was not really understanding what people are thinking. Everybody coming from so many different places, so many different experiences, everybody looking at the same things in completely different ways.” We are a nation of people whose family trees have been transplanted. Our histories have been interrupted, and we often are confused about where we fit in. Reflecting this, Akhtar challenges the idea of the melting pot. As an alternative, he borrows an idea from chemistry and he asserts that the country is a “buffer solution – which keep things together but always separated. That’s what this country is. A buffer solution.”

In the words of one of his characters Akhtar says, “The thing I never got used to here was not really understanding what people are thinking. Everybody coming from so many different places, so many different experiences, everybody looking at the same things in completely different ways.” We are a nation of people whose family trees have been transplanted. Our histories have been interrupted, and we often are confused about where we fit in. Reflecting this, Akhtar challenges the idea of the melting pot. As an alternative, he borrows an idea from chemistry and he asserts that the country is a “buffer solution – which keep things together but always separated. That’s what this country is. A buffer solution.”

Akhtar’s deft storytelling in Homeland Elegies streams together the story of a father, born in Pakistan and making his way in the United States, and a son born and raised in the United States, but still puzzled about his connection to another place where there are people and habits that resonate deeply with his own primordial sense of “family.” The father in Akhtar’s story, a physician lured by the dream of being both a healer and an entrepreneur, finds both boom and bust in his fearless pursuit of the American Dream. He takes his chances, and the gamble undoes him.

The son in Akhtar’s story is his father’s opposite. He grows up in the United States, culturally nurtured on the advice to follow your own dreams. He is determined to be a writer, does well in school, and immerses himself in creative ventures, which for a time require that he live on loans and handouts from his father. The plays he writes and the fiction he weaves reveal the puzzles and complexities of the immigrant experience. He reveals the insults of being judged by the color of his skin or his name, the insults born for being Muslim, and his confusion about the meaning of wealth and success in America.

In the eyes of his father, the son is a wastrel who is failing to embrace the opportunities of the American Dream. With so many opportunities available to him, the father cannot understood why his son would squander his options for the luxury of telling tales about the people in his life. Even after the son becomes successful, his father remains disappointed with what he considers a lack of ambition. Why would his son want to be a writer?

With so many opportunities available to him, the father cannot understood why his son would squander his options for the luxury of telling tales about the people in his life. Even after the son becomes successful, his father remains disappointed with what he considers a lack of ambition. Why would his son want to be a writer?

Akhtar masterfully portrays the way children born in the United States to immigrant parents, live in two cultures and form a double-consciousness. What other children assume, these children must assert. A name, a religion, a skin-tone, and sometimes the bald prejudice of others are relentless reminders of another identity. For Akhtar the moment of assertion comes when he is already a successful writer and making a public presentation. A member of the audience takes exception to comments he has made about the role of the arts in addressing social problems. His interlocuter suggests that if Akhtar doesn’t like the way things are in America, he should go somewhere else.

“It took me a moment to speak: I didn’t expect to be emotional, but I was,” Akhtar writes. It is a break-through moment. “I’m here because I was born and raised here. This is where I’ve lived my whole life. For better, for worse – and it’s always a bit of both – I don’t want to be anywhere else. I’ve never even thought about it. America is my home.” Who but someone aware that others see him as an outsider needs to make this assertion for himself?

The son of Akhtar’s story, who asserts his American identity, is witness to the fact that his father has never been truly at home in the United States. Akhtar says of his father: “As much as he’d always wanted to think of himself as American, the truth was he’d only ever aspired to the condition . . . . he’s been playing a role so much of that time, a role he’d taken as real.”

Immigration creates misalignment in the relationships of parents and children. They feel embarrassment for each other in places where, each in their own way, they are not understood: the parent in the new country, and the child in the old country. They are also witnesses to each other’s sadness. The child sees the parent’s rejection and feels pain for losses that are inevitable. Even for the immigrant who embraces the new home wholeheartedly, it is a “cruel paradise.”* Even the most assimilated immigrant is shadowed by consciousness of being an outsider.

The children of immigrants know a world that is not their world anymore, but it is still the world of people they know and cherish. In the old familiar places from which the family has come, the child born in America will always be a visitor, welcomed and doted on, but a visitor nonetheless. Inside the immigrant household, settled in America, there are layers of life that are strange beyond its walls. The immigrant child, crossing the threshold of the house while coming and going from home day by day, is crossing cultural borders. It is not possible to transplant homes and home places. The immigrant child is always, to some degree, an emotional nomad.

In a stirring scene toward the end of Homeland Elegies, as the son says farewell to a father who is returning home to his place of birth, both the pain and the love are evident. The weeping son tells his father he is sorry. “I didn’t know what I was apologizing for, but I knew I had to apologize,” he says. His father does not accept his apology. “No, no . . . ,” the father says. But the son needs to be heard. He grabs his father’s coat and pulls him toward him, while the father is still objecting. “. . . I pressed in and drew him closer, pressing myself to him, feeling him as tightly against my body as I could. I held him there until he stopped resisting. It wasn’t until he tried to speak that I realized he was also crying now. . . . Only the embrace between us mattered now. If only I could hold him close . . .hold him longer. Maybe what was broken in both of us could finally be mended.”

Many immigration stories are either victim stories or resentment stories. They focus on the undeniable hardships of immigration or the injustices acted out on those who are judged by others to be outsiders. Both of these are true to the experience of immigration, but there are additional elements in Akhtar’s account, and that is the merit of his story. He does not destroy the bond between father and son even as he narrates its difficulties. Instead he brings into view the indescribable sadness of immigration as it creates irreparable separation between the generations.

The sadness of immigration is felt in the second generation when children look at their parents who remain alien no matter how long they have lived in American and no matter how hard they have tried to fit in. They may be citizens, they may be taxpayers, they may vote, they may serve in the military, they may be eligible for social security, and eventually they may be buried in American soil, but they will always be partly alien. They will never be as completely American as they assume other Americans are. That is the sadness of immigrant children. The title of Ayad Akhtar’s novel is accurate. It is an elegy. It is a sobering reflection on something that has passed away and is gone.

Akhtar’s novel is autofiction: the protagonist has the author’s name, and many of the elements of the story parallel events in the author’s own life. Despite this Akhtar deftly avoids the blunders so common in this genre. He does not conceal himself behind the excuse that his self-revelations are “only fiction.” Whether they are identical to the particulars of his life, they are true to the experience of his life. He writes with the forthrightness of someone who has been cut on the sharp edges of immigration. So is Akhtar’s writing fiction or memoir? Who cares? The writing is fluid and lean. The story is frank and colorful. And within a few pages the reader is hooked. The story deserves to be read. It surfaces so much that Americans need to be considering with each other.

*Hylke Speerstra and Henry Baron, Cruel Paradise, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2005.

author Peter de Smet has captured a spot in the genre with The Secret Life of Hendrik Groen, 83 ¼ years old. After first holding a place for over thirty weeks on the bestseller list in the Netherlands, it has now been released in twenty-one other countries, along with its sequel On the Bright Side: The New Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen, 85 years old. Each of these authors has gotten rave reviews.

author Peter de Smet has captured a spot in the genre with The Secret Life of Hendrik Groen, 83 ¼ years old. After first holding a place for over thirty weeks on the bestseller list in the Netherlands, it has now been released in twenty-one other countries, along with its sequel On the Bright Side: The New Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen, 85 years old. Each of these authors has gotten rave reviews.

In 2017 when Elizabeth Berg wrote The Story of Arthur Truluv, she herself was seventy years old. She understands the meaning of loss that comes with age. Her novel has depth that some of the others in the genre lack. She also understands that loss does not begin with age, and she creates a touching alliance between a colorful young woman and two older adults. Berg makes it clear that they need each other. Her writing mixes humor with compassion. It is not a mushy novel; it’s a respectful one. We might even call it “age appropriate.”

In 2017 when Elizabeth Berg wrote The Story of Arthur Truluv, she herself was seventy years old. She understands the meaning of loss that comes with age. Her novel has depth that some of the others in the genre lack. She also understands that loss does not begin with age, and she creates a touching alliance between a colorful young woman and two older adults. Berg makes it clear that they need each other. Her writing mixes humor with compassion. It is not a mushy novel; it’s a respectful one. We might even call it “age appropriate.”

With this adventure in historical detective work built around the discovery of a lost document, Kadish joins a guild of talented writers like Geraldine Brooks (People of the Book) and Stephen Greenblatt (The Swerve) who can turn obsession with a manuscript into a gorgeous historical portrait.

With this adventure in historical detective work built around the discovery of a lost document, Kadish joins a guild of talented writers like Geraldine Brooks (People of the Book) and Stephen Greenblatt (The Swerve) who can turn obsession with a manuscript into a gorgeous historical portrait. everywhere. In sidebars seamlessly woven into the story, Kadish creates a portrait of seventeenth century households in which women were responsible for the grinding labor of laundry, food preparation, and keeping the fires for cooking and heating continuously tended. In a time of disaster the difficulty of all these duties was multiplied. If life was hard in general, it is unspeakably hard for women.

everywhere. In sidebars seamlessly woven into the story, Kadish creates a portrait of seventeenth century households in which women were responsible for the grinding labor of laundry, food preparation, and keeping the fires for cooking and heating continuously tended. In a time of disaster the difficulty of all these duties was multiplied. If life was hard in general, it is unspeakably hard for women. Will the time return when we can hug and kiss friends and relatives at funerals and dance with friends and family at weddings? Will choirs again sing together without fearing that along with projecting beauty they are spreading death?

Will the time return when we can hug and kiss friends and relatives at funerals and dance with friends and family at weddings? Will choirs again sing together without fearing that along with projecting beauty they are spreading death?

It was customary at the time for a widow to dress in black for two years after the death of her husband, but Sarah never gave up her mourning attire. A look at her life would suggest her choice to remain a perpetual widow was less a gesture of grief and more a signal to suitors that she had turned her attention to matters more important to her than marriage.

It was customary at the time for a widow to dress in black for two years after the death of her husband, but Sarah never gave up her mourning attire. A look at her life would suggest her choice to remain a perpetual widow was less a gesture of grief and more a signal to suitors that she had turned her attention to matters more important to her than marriage. In June, at Gettysburg, there had been a battle so bloody it became known as the Harvest of Death, and the invention of photography brought images of the horror to the public.

In June, at Gettysburg, there had been a battle so bloody it became known as the Harvest of Death, and the invention of photography brought images of the horror to the public.

Costumes for pets is a growing trend. Animals don’t concern themselves with how they are dressed for Halloween, or whether they are costumed at all, but apparently their owners care. Pets, especially dogs, have become surrogate children, and Halloween is their holiday too.

Costumes for pets is a growing trend. Animals don’t concern themselves with how they are dressed for Halloween, or whether they are costumed at all, but apparently their owners care. Pets, especially dogs, have become surrogate children, and Halloween is their holiday too.